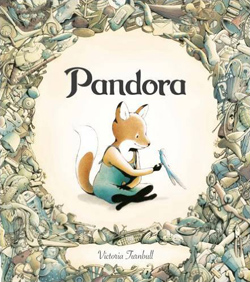

Victoria Turnbull graduated with an MA in Children’s Book Illustration from Cambridge School of Art. Her debut picturebook, ‘The Sea Tiger’ (originally a college project), was shortlisted for the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize and nominated for the prestigious CILIP Kate Greenaway Medal. Victoria lives and works in London. In this post, Victoria talks about her third picturebook, ‘Pandora’. This stunningly illustrated tale of hope and regeneration was originally published in the UK by Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, and has been translated into several other languages.

Victoria:‘Pandora’ is the third picture book I’ve both written and illustrated. My first two books were developed on my MA in Children’s Book Illustration and published consecutively after finishing the course. So this was the first one I’d written outside the sanctuary of the MA, and it felt like a big step.

The seed of the story was planted after reading a news story about recently discovered cave paintings, where footprints of a child and a fox were also found. I began to imagine a world where man no longer existed, yet one where his former existence was evident in all the things he’d left behind. In this grey desolate landscape of rubbish I was starting to picture, a fox seemed like a natural protagonist. The fox has become a feature of our urban landscape and I felt this enigmatic creature would adapt well to a man-made environment.

‘Pandora’ was always a story of regeneration. Whenever I considered it, an image would pop into my head of a vast landscape of waste mountains that transformed into rolling hills at the turn of a page. Visually it felt like a satisfying conclusion and if I could figure out the catalyst for the change, it also told me how the story would end.

I searched for influences to fit this idea in the form of other stories, such as ‘Pandora’s Box’ and ‘Noah’s Ark’. Around this time, I also rediscovered a book of fairy tales from my childhood. In ‘The Nightingale’ by Hans Christian Andersen, an Emperor prefers the song of a mechanical bird to that of a real nightingale – only realising his mistake when he’s close to death. The story echoes the notion of mankind valuing material possessions over the natural world and added to the connections that were starting to form in my mind. Eventually these thoughts tumbled out onto a page in my sketchbook.

I came to picture book making through my love of drawing, and I still find creating a narrative an incredibly difficult process. By this stage I had an idea of the shape of the story but I didn’t know how it was going to fit into a 32-page format. In an effort to organise my thoughts, I started laying it out as thumbnails. In one of my early drafts, Pandora constructs a mechanical bird out of the objects she finds on the dump and the bird brings back seeds that transform her landscape. It seemed like a neat solution but I felt something was missing.

At the heart of all my stories is a search for something: a journey of self-discovery where the character finds the inner strength needed along the way. Pandora’s story only became clear when I realised, like the Emperor in ‘The Nightingale’, she wouldn’t be happy with an imitation of nature. She needed a real connection. Once I decided a wounded bird would come into Pandora’s world, the narrative fell into place much more easily.

I worked on the text and the illustrations simultaneously, adding corresponding text to my sequential drawings to show what was happening in each panel. The text reflects Pandora’s limited understanding of her world and serves to enhance her feelings of isolation. It changed very little from here to the final book.

I submitted the final storyboard alongside a couple of character sketches to my publisher and they liked the concept, so I was able to start work on the roughs. At this stage, compositions can easily change so I don’t like to invest too much time in the drawings. I try to keep them quite loose, so there’s still more for me to discover when creating the final artwork.

Sometimes a character just speaks to me in some way, and that’s how it was with Pandora. I really empathised with this little fox and I wanted that feeling to come across in the drawings.

I thought Pandora should look small and vulnerable in relation to the environment, so I proportioned her like a child and put her in a dress that allowed her tail to poke out from underneath. I also liked the way her markings gave the appearance that she was wearing socks. When I draw, I’m often looking for something elusive, a feeling I get when I know it’s right. It usually takes many failed attempts but it’s exhilarating when it happens.

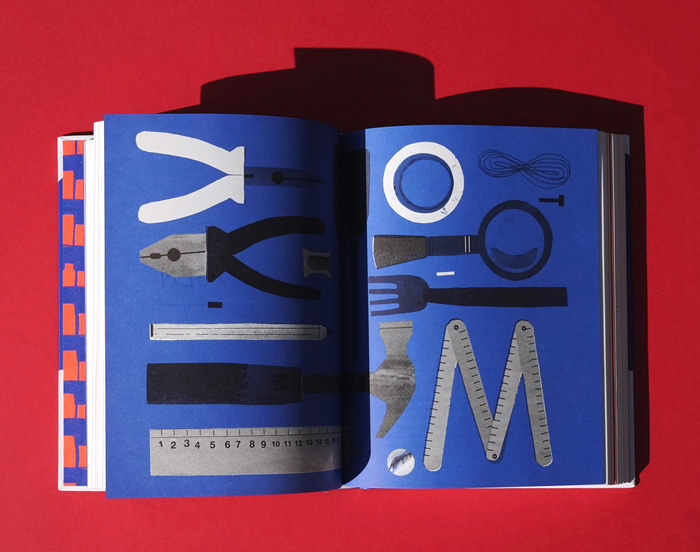

I felt emotionally invested in telling this story and I wanted to do that as best as I could. My concern was that setting a picture book on a rubbish dump could potentially feel a little depressing. I also much prefer to draw natural forms than man-made objects but there was nothing I could do to avoid it here. So just as Pandora manages to bring beauty into her imperfect world, I endeavored to find little things of interest to love as I created the pictures.

My first step was to go to various London museums to photograph all the things that seemed to belong in this world I was creating. I wanted it to look alien yet familiar, so I tried to choose objects that reflected this. My hope was by introducing lots of detail, the reader would be forced to stop and consider the environment. But as a consequence, it also made me consider the areas of white space and how important it was for the book to work as a whole.

I try to adapt my technique to each narrative. For this book, I knew I wanted very little colour in the initial pages, with gradually more colour creeping in as the story progresses and as nature prevails. In an effort to preserve the spontaneity of my original sketches, I scanned and printed out my pencil drawings onto thick paper. These line drawings were then coloured with a combination of graphite pencil, coloured pencil, pastel and linseed oil. Creating the artwork by hand is quite a laborious process, and after straining my arm, I struggled to complete the final few spreads. But I think in the end it was worth it.

For me, ‘Pandora’ is a story of hope and humanity. Even though man doesn’t appear in the book, he is always present. Children have an innate sense of wonder and curiosity in the natural world, but it’s easy to lose that connection as we grow older. I hope the reader takes from this book the knowledge that they can affect their own story, and the story of the world they inhabit.

Illustrations © Victoria Turnbull.

Pandora

Victoria Turnbull

Frances Lincoln, United Kingdom, 2016

Pandora lives alone in a land of broken things. She makes herself a handsome home from all that people had left behind, but no one ever comes to visit. One day, a bird with a broken wing falls from the sky. Pandora nurses the bird back to health, and it begins to fly away each day, bringing back seeds and small plants. When the bird stops coming, Pandora is heartbroken. But day by day, things begin to grow…

A beautiful tale of hope and regeneration.